Was the War on Drugs Effective?

The War on Drugs was supposed to systematically dismantle drug smuggling rings that were spreading their products in the United States. With military operations abroad and zero-tolerance policies at home, the illegal drug industry should have been squeezed into submission. But despite literally trillions of dollars being spent on preventative and punitive measures, every conceivable measure of gauging the effectiveness of the War on Drugs has ruled it a failure.

Bring Back the War

William J. Bennett and John P. Walters, former Directors for the Office of National Drug Control Policy under Presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush, respectively, co-wrote an op-ed in the Boston Globe called “Bring Back the War on Drugs.” Pointing to the wave of fatalities brought about by opioid overdoses (fueled by overprescription of painkillers, which gives way to heroin abuse), Walters claims that treatment and rehabilitation will neither prevent people from experimenting with hard drugs nor truly help patients achieve sobriety.

Now, Walters and Bennett write, “death and addiction spread” throughout American communities and cities. Before Barack Obama refocused anti-drug efforts in the United States, a quarter-century of government policy confronted the drug problem head on, creating programs that targeted the production, distribution, and industry of illegal substances. “It worked,” declares Walters.[1]

Goals Met: Zero

In 2010, NBC News wrote that the War on Drugs “has met none of its goals,” specifically mentioning the widespread use of illegal substances, and rampant violence and crime, as evidence that the lofty goals put forward in the declaration of the War have fallen far short.[2]

One of the problems, said Gil Kerlikowske, the former Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, is that the US government never took a big picture approach to the problem of drugs. There was too much of a focus on arresting drug dealers and not enough on treating the addiction that made drug dealing such a lucrative business.

Public Enemy Number One

However, hindsight is 20/20. When President Richard Nixon declared the War on Drugs in 1970, there was no concept of considering drug users as people in need of help. In the early 1970s, the faces of substance abuse were hippies smoking pot, experimenting with harder drugs, and protesting the Vietnam War. Fifteen percent of active soldiers in Vietnam were addicted to heroin, a statistic that cast grave doubts on Nixon’s promises to end the war, as well as his ability to control rising crime rates at home.[3]

When he passed the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act in 1970, Nixon labeled drug abuse as “public enemy No. 1 in the United States,” and pledged to wage an all-out offensive. He allocated $100 million to the cause. In 2010, the drug-fighting budget has ballooned to $15.1 billion, 31 times Nixon’s original amount, even when inflation is taken into account.

Billing the War on Drugs

How could it cost the country with the best technology, military intelligence, and worldwide influence literally tens of billions of dollars to crack gangs and smuggling rings in developing countries? The Associated Press dug deep and found that the government increased budgets for programs that were ineffective in stemming the flow of drugs into the country. In the last 40 years, the money has gone in a number of different directions:

- $33 billion in domestic marketing, such as Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign: While the campaign did contribute to a drop in rates of teenage drug use, it was also criticized for reducing a multifaceted public health crisis to nothing more than a slogan.[4], [5]

- $20 billion to counter, and combat, drug cartels on their own turf: The United States spent $6 billion to break up operations in Columbia; in response, the trafficking moved to Mexico, leading to the Mexican government being unable to control the organized crime syndicates in their own country.[6] In Ciudad Juarez – the former “murder capital of the world” – 2,600 people were killed in 2009 by drug cartels vying for power and dominance.[7]

- $49 billion to fund law enforcement and border control missions on the southern border: This covers just under 2,000 miles from California to Texas. It entails providing resources for patrols, sniffer dogs, checkpoints, cameras, motion detectors, heat sensors, drone aircraft, and over 1,000 miles of steel beam, concrete walls and heavy mesh along the border. Nonetheless, the 330 tons of cocaine, the 20 tons of heroin, and the 110 tons of methamphetamine that are sold in America every year, which are consumed by 25 million Americans, are mostly smuggled over the Mexican border.

- $121 billion to arrest more than 37 million drug offenders for low-level, nonviolent crime and $450 billion to process them in federal prisons: Even though the The Washington Post writes that the mindset of throwing drug users in jail (which has “characterized the failed war on drugs”) ignores the reality of drug addiction in prison, hundreds of billions of dollars have been allocated to these efforts.[8]

‘No Effect on Reducing Drug Use’

Looking at the numbers, an economist from Harvard University says that the only guarantee taxpayers get for funding police and military operations to curb drug trafficking are increasing rates of crime and death. The current policy has no effect on reducing drug use, he says, even as it costs the American public a fortune.

The Justice Department provides a further estimate, taking into account the economic consequences of drug abuse on the criminal justice system, the healthcare system, the job market, and even “environmental destruction.” Drug addiction costs the United States $215 billion every year.

The impact of the War on Drugs on the criminal justice system is one measure of the failure of the program. So overwhelming are the number of cases that US prosecutors have to process for all the arrests made, that attorneys declined to file charges in 25 percent of drug cases – 7,482 in 2009 – just because they didn’t have the time.

The Unquenching Thirst

Expenses caused by the War on Drugs are in the hundreds of billions of dollars, but even that pales in comparison with the $320 billion made every year by the illegal drug industry. That figure accounts for 1 percent of all commerce taking place across the world, and it is far ahead of the other lucrative criminal enterprises of counterfeiting ($250 billion) and human trafficking ($31.6 billion).[9]

Ten percent of Mexico’s entire economy is based on money from drug smuggling, $25 billion of which comes from sending cocaine, heroin, marijuana, and methamphetamines over the California-Texas border. Business is so astronomical that there is no concept of offering the cartels any form of financial incentive to change their ways. Even former Mexican President Felipe Calderon is on record as saying that if the United States wants to seriously address the topic of drugs, the government needs to address “Americans’ unquenching thirst” for contraband substances.[10]

Law Enforcement against the War

Walter McCay, the head of the Center for Professional Police Certification in Mexico City explains that every drug dealer has a line of people waiting to replace him when he is inevitably taken out of the picture, whether by incarceration or death. The promise of money from the cartels far outweighs any other obligation.

Walter McCay, the head of the Center for Professional Police Certification in Mexico City explains that every drug dealer has a line of people waiting to replace him when he is inevitably taken out of the picture, whether by incarceration or death. The promise of money from the cartels far outweighs any other obligation.

McCay is also a member of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, a 13,000-strong group of police officers, judges, lawyers, prison wardens, and other people in the law enforcement/criminal justice system, who are calling for the legalization and regulation of all drugs. The strength of such a group – let alone its existence – points at how far the pendulum has swung on the War on Drugs. The idea of a lobby of people, whose job it is to uphold the law and punish those who break it, calling for a more progressive, realistic approach to dealing with the saturation of drugs (and the resultant economic and human cost), would have been unthinkable a decade ago.

Before meeting with President Barack Obama to discuss improved initiatives to crack down on crime and incarceration rates, the police chiefs of Houston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York called the War on Drugs “a tremendous failure,” because of how decades’ worth of flawed programs have scapegoated people with no money, no education, no job skills, and no resources with which to secure effective legal representation. More often than not, those people come from ethnic minority communities, which has contributed to perceptions of systematic and institutionalized racism from law enforcement, which has, in turn, made American cities more dangerous.[11]

The Punishment Model

A lot of things have changed since the order of the day was “zero tolerance” and being “tough on crime.” A 2013 study published in the British Journal of Medicine found that drug prices have fallen since 1990, and the chemical purity of those drugs has increased, making a mockery of the tens of billions of dollars spent every year to prevent that from happening. In the study, the authors wrote that the strategy of trying to control the global drug market by way of law enforcement is failing.[12]

In the words of The Guardian, the War on Drugs represents a “systematic failure of policy.”[13] Policies were the focus of a 2008 report by the Brookings Institution, which compared how various countries treated their citizens for drug infractions. The United States’ “punishment model,” which favors incarceration as a form of deterrent, was criticized for leading to an explosion in incarceration rates; 50,000 people were sentenced to prison terms in 1980, which ballooned up to 210,000 people in 2015. However, only a small number of those people were given any treatment for the drug problems that contributed to their arrest.

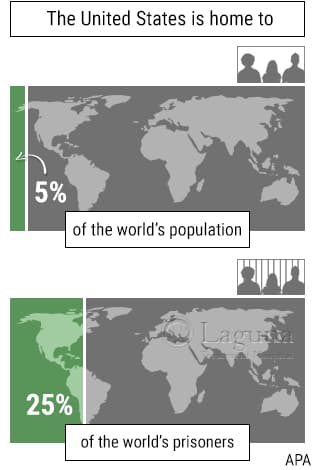

The American Psychological Association writes of “incarceration nation,” the country home to 5 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of the world’s prisoners, most of whom are poor, uneducated, with minimal job skills, and of minority descent, a result of disproportionate targeting by law enforcement. A psychology professor at George Mason University tells the APA that the “punishment model” is “very costly,” offering only a few benefits and many damaging effects on the economy, families, and communities across the country.[14]

Other models surveyed by the Brookings Institution, such as the “depenalization model” of Italy and Spain (narcotics are illegal, but personal use from individual possession is not illegal) and the “decriminalization model” in the Netherlands (cannabis can be legally purchased for personal use) were reviewed more favorably.[15]

The Stakes Are Too High – Janet Napolitano

John Carnevale, an economist and expert on drug policies, who served three presidential administrations and the four directors of drug control policies they respectively established, told NBC News that despite the change in rhetoric and overwhelming evidence of the failure of the War on Drugs, recent and current administrations persist with spending too much money on the areas that have been proven to be least effective, and too little money on those that offer the most promise.

For example, in 2010, President Barack Obama requested $15.5 billion – a record amount – from Congress to fight trafficking and smuggling. Sixty-six percent of that money would go to border patrol, police, and military on the southern border. Only $5.6 billion was allocated for the mental health dynamic of treatment and prevention.

Speaking at the US embassy in Mexico City, Janet Napolitano, the former Secretary for Homeland Security, was asked in 2010 why the United States persisted with expensive programs that have been proven to be unsuccessful. Napolitano framed the deadlock in terms of fighting for people’s lives and their futures, which, by extension, makes the drug war worth fighting. In Mexico – which the Seattle Times writes is a victim of America’s drug addiction – the fight for people’s lives is all too literal, and “you realize the stakes are too high to let go.”[16]

The War on People

The idea of treating drug addiction as a public health problem, and not one of crime and punishment, is gaining traction, but it is a relatively new idea. That is because the perspective of drug users as morally corrupt troublemakers (who were, more often than not, from a different ethnic group than the majority) existed for generations, so much so that it fed into Richard Nixon’s declaration of the War on Drugs, and influenced how the public and the government looked at people who were addicted.

As far back as 1914, the myth of the “Negro cocaine fiend” spread the idea that black people were prone to hallucinations, acts of violence, and homicide when under the influence of cocaine. The New York Times carried the story, which firmly imprinted the connection into the minds of the general public that there was an inherent relationship between drugs, black people (especially poor black people), and crime.

The Nation writes that the “Negro cocaine fiend” hysteria influenced American drug policy for decades to come.[17] When race relations were at a tipping point in the late 1960s, and the Vietnam War was looking like a lost cause, Richard Nixon – who had a deep-seated disdain for drugs – found the perfect target to start a new war.[18]

‘Lying about the Drugs’

That war, said John Ehrlichman, Domestic Affairs Advisor to the Nixon administration, was targeted at Nixon’s two enemies: Vietnam War opponents and black people. Since the administration couldn’t directly target black people or the “antiwar left,” the decision was made to create a connection in the court of public opinion, between “the hippies with marijuana” and “the black with heroin.” By criminalizing across the board, the two communities – both thorns in Nixon’s side – would be disrupted, their leaders arrested, their privacy violated, and their reputations ruined.

“Did we know we were lying about the drugs?” Ehrlichman asked rhetorically. “Of course we did.”[19]

Disastrous Consequences

If this was the real casus belli behind the War on Drugs, then the effect it had was to make black Americans much more likely to be arrested for using or selling drugs, even though, in the words of The Huffington Post, it’s “white America [that] does the crime.”[20] The Post quoted sources that suggested that white Americans commit even more drug-related crime than black Americans, but have the benefits of being able to access better legal representation than the typically poorer demographic targeted by police for drug busts.[21]

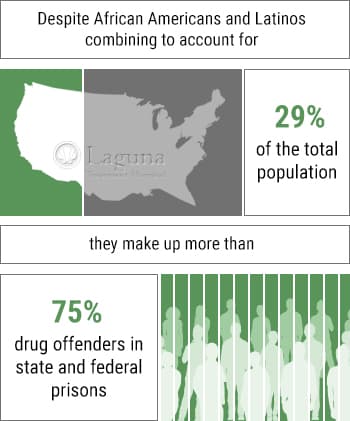

Another article from The Huffington Post condemns the War on Drugs for being based on racial injustice. African Americans are arrested 13 times more than white Americans for drug use, “despite roughly equal rates of drug use and sales.” In some states, that ratio rises to as high as 57 percent. Despite African Americans and Latinos combining to account for 29 percent of the total population of the United States (as of 2013), they make up more than 75 percent of drug offenders in state and federal prisons. The Post lists this as one of “10 disastrous consequences” of the War on Drugs.[22]

To that effect, a 2012 report from the US Sentencing Commission found that when black Americans are convicted of drug-related offenses, they are given longer prison sentences than white Americans receive for the same crime.[23] This, says John Ehrlichman, was not an unforeseen consequence of the War on Drugs, but the goal.

Rethinking the Drug War

Nixon taking aim at counterculture communities seemed like a good idea at the time. In 1969, two years before he announced the implementation of the policies of the War on Drugs, a Gallup poll found that only 12 percent of the public was in favor of legalizing marijuana. But times were changing: by the end of the 1970s, support was already increasing; and by the turn of the millennium, support had passed 30 percent. In 2015, 58 percent of survey respondents agreed with the legalization of marijuana for recreational use.[24]

The trend suggests a significant cultural shift in perceptions of crime and punishment when it comes to drugs. The Pew Research project found that with falling rates of violent crime, and the economic effects of the Great Recession, the public is less keen on seeing the prosecution of minor, low-level and nonviolent drug offences, causing the federal government to “[rethink] the Drug War.”[25]

In writing on “America’s New Drug Policy Landscape” in 2014, Pew revealed that 67 percent of Americans would prefer the government to provide treatment for people who use illegal drugs and not prosecute them. By contrast, just 26 percent of respondents to Pew’s survey chose criminal punishment over treatment.[26]

Where the people go, the politicians follow. In the buildup to the 2016 United States presidential elections, nearly every candidate from both parties expressed a desire to adopt smarter policies in the fight against drugs. New Jersey’s governor Chris Christie called the War on Drugs an “abject failure.”[27] Former First Lady and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton signaled her intention to focus on improving mental health and drug treatment policies in her hypothetical presidency.[28] Rick Santorum walked back from his previous belief in the zero-tolerance policies of the War on Drugs and called for the criminal justice system to be reformed instead.[29] Rand Paul is a sponsor of the RESET bill (Reclassification to Ensure Smarter Treatment), which recategorizes minor drug offenses down from a felony to a misdemeanor. Rand also coauthored the Justice Safety Valve Act, giving judges greater discretion in deciding the punishment for minor drug-related crimes, specifically targeting mandatory minimum sentencing discrepancies.[30]

Mandatory Minimum Sentencing

Discrepancies surrounding mandatory minimum sentencing have long been held as one of the most deleterious effects of the War on Drugs. The term refers to the practice of there being unfair sentencing guidelines for drug users arrested for possessing crack cocaine; such people are confronted with much harsher penalties, than those who are arrested for possession of powdered cocaine, even though the difference between the two substances (in terms of their addictive effects) is minimal.

Discrepancies surrounding mandatory minimum sentencing have long been held as one of the most deleterious effects of the War on Drugs. The term refers to the practice of there being unfair sentencing guidelines for drug users arrested for possessing crack cocaine; such people are confronted with much harsher penalties, than those who are arrested for possession of powdered cocaine, even though the difference between the two substances (in terms of their addictive effects) is minimal.

For example, a person arrested for possessing 5 grams of crack cocaine would be sentenced to a mandatory minimum prison sentence of five years. A person arrested for possessing powdered cocaine would have to have been arrested with 500 grams, in order to be sentenced to five years. It would require 10 grams of crack cocaine for a person to be sentenced to 10 years in prison; but a person carrying powdered cocaine would have to be carrying 1,000 grams for the same sentence to apply.[31]

But as long ago as 1997, a study found that neither crack cocaine, nor powdered cocaine, was more addictive than the other.[32] The Los Angeles Times claimed that there was never any scientific basis for treating either drug differently in the eyes of the law.[33] Forbesattributes the unfair effects of mandatory minimum sentencing to the “out of control War on Drugs,” and The Washington Post cited “the drug war’s failures” as a reason for Congress to reform mandatory minimum sentencing laws.[34],

Fighting a New War

The conflict of how to approach the fight against drugs, while not endorsing the widespread damage caused by the War on Drugs, was demonstrated by Gil Kerlikowske, the former Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, calling for the term War on Drugs to be retired, saying that it sends out a wrong, outdated message. On the other hand, the new method of considering the drug epidemic as more of a public health issue (as opposed to a criminal justice one) would be more successful in reducing drug use at home, and depriving cartels and drug rings abroad of their most lucrative marketplace.[35]

Speaking primarily of local issues, Minnesota Public Radio declared in April 2016 that “the War on Drugs hasn’t worked,” because of how the zero-tolerance policies of the War disproportionately singled out economically vulnerable and disenfranchised populations – primarily, low-income people and ethnic minority groups – while ignoring or sheltering drug abusers in affluent communities. MPR spoke highly of drug court systems in Ohio and Minnesota, which incentivized substance abusers to enter treatment and rehabilitation programs (with the promise of a clean record at the conclusion of their sentence).[36]

Has the War on Drugs Failed?

The War on Drugs should have sounded the death knell for the illegal drug trade that has wreaked havoc across the globe, led to the deaths of millions of people, and ruined the entire way of life for developing countries. The Huffington Post bleakly notes that in the face of unaffected addiction rates, high overdose rates and the low cost of drugs, the War “has failed in every way possible.”[37] CNN called it a “trillion dollar failure.”[38] The Daily Caller writes that the federal government have “failed every goal set” in the War, making no progress in any of the stated aims to deal decisive blows to drug cartels and reduce the number of overdose deaths. The Government Accountability Office found that in some areas, the United States has actually made the situation worse. The Deputy Director of the Drug Policy Alliance stated that “harm reduction and treatment are woefully underfunded,” while $2 billion is spent every year to fund the Drug Enforcement Administration, which is a “failed and flawed agency.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the legal drug industry is also of the opinion that the War on Drugs has been spectacularly ineffective. The CEO of Terra Tech, a cannabis-focused agriculture company, tells the Caller that the War on Drugs has failed in the past, is failing in the present, and will most likely fail in the future.[39]